Why technology is the only way to liberate animals

Could engineers be the most successful animal rights activists in history?

Meat production is the last bastion of animal subjugation still deeply embedded in modern western society. Historical precedent suggests that technology — not morality alone — has been the force most capable of moving humanity beyond the systematic exploitation of animals. Yet new technologies do not automatically lead to progress. They are instruments. Whether they liberate or destroy depends on how, where and for whom they are deployed.

The original stock market

Imagine you are a villager in an early pastoral society. If you owned twenty animals, you were probably doing alright. Animals, particularly larger ones, were a store of wealth. The word capital comes from the Latin caput, meaning head – wealth was once measured by heads of livestock.

Today, we have more convenient ways to store and exchange wealth. Money – both physical and digital – has rendered livestock as currency obsolete. This is evidently for the best. I don’t imagine cows make the tidiest of flatmates, and it would be rather inconvenient to take a chicken along to the petrol station to exchange for a full tank (although at today’s prices, one lamb might be closer to the mark).

Technological innovation has gradually replaced the roles animals once played in human economies – as transport, labour, materials and food. To speak of animals in terms of “function” is, of course, to adopt a distinctly human lens; animals do not exist for us. They exist within ecosystems, as natural beings in their own right. Today, only two enduring relationships remain: animals raised for meat and animals kept as companions. The former is defined by exploitation; the latter, at its best, by affection. Recognising how technology has displaced animals’ economic utility helps us see how it might one day release them from the final forms of exploitation that persist – most significantly in the production of meat and other animal-derived foods.

Oil’s well that ends whale

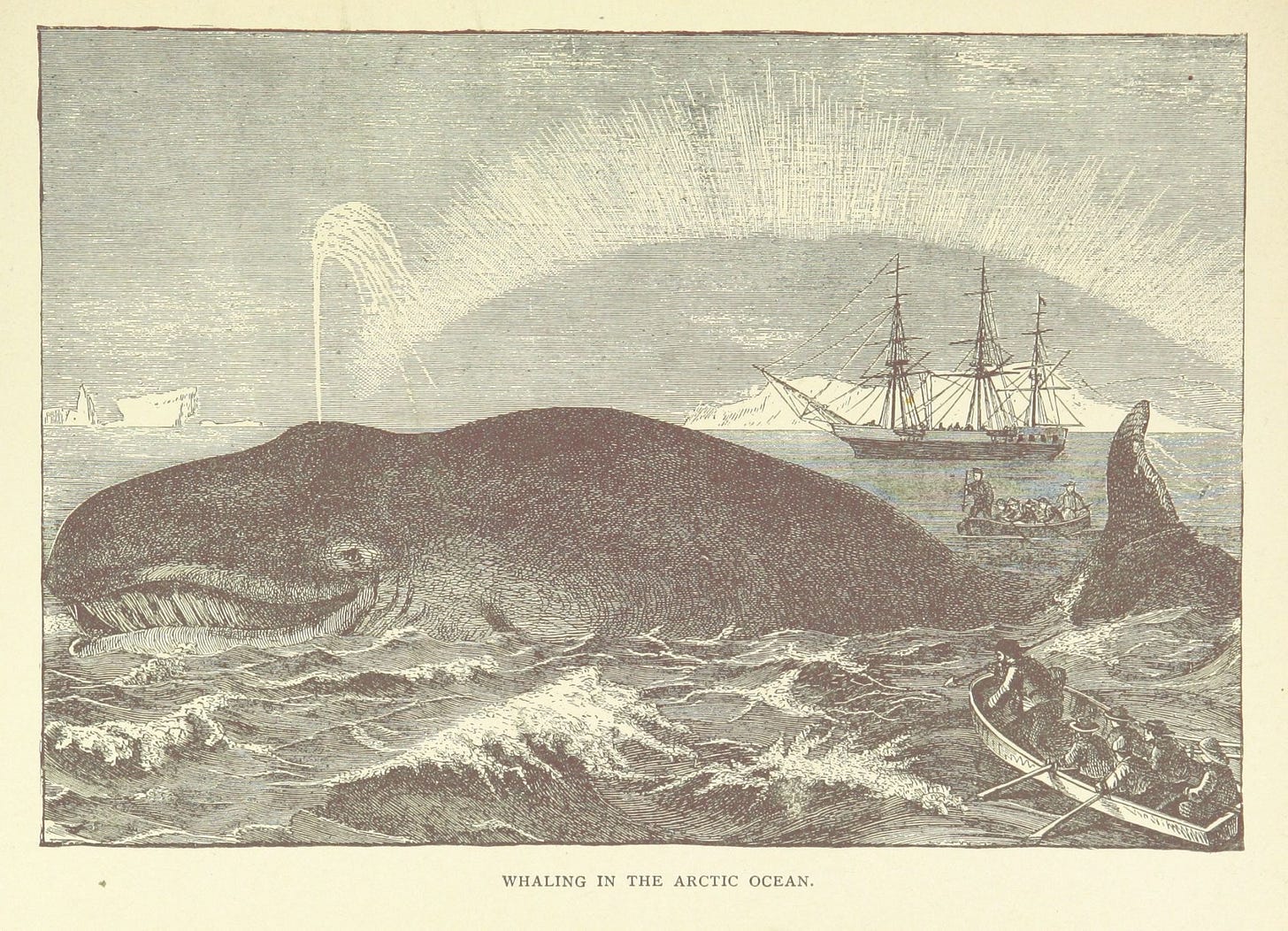

Fossil fuels get a bad reputation these days, which seems fair given they are largely responsible – alongside the humans who extract and burn them – for the prospect that our planet could become uninhabitable within a century. Yet from an animal rights standpoint, they once offered an unexpected reprieve.

By the mid-19th century, kerosene – distilled from petroleum – had eclipsed whale oil as the preferred lamp fuel. It was cheaper, cleaner and plentiful, and its arrival briefly spared whales from relentless hunting. For a moment, technology liberated them – but by accident, not by design.

The inventors of kerosene were not thinking of whales; they were thinking of brighter lamps and cheaper light. Yet their discovery achieved, momentarily, what moral campaigning could not. When the whale-oil market collapsed, the whaling industry simply reinvented itself – diversifying into margarine, soap, lubricants, cosmetics and fertilisers, as well as whale meat for both human and animal consumption. Petroleum, meanwhile, powered the industrial technologies that would take whaling to new extremes: steamships, explosive harpoons and factory ships capable of processing carcasses at sea. By the 1960s, around 80,000 whales were being slaughtered each year.

Ultimately, it was not technology but international cooperation and moral intervention that saved whales from extinction. Treaties and whaling bans, grounded in an emerging sense of ethical and ecological responsibility, achieved what earlier technological progress had failed to do.

The lesson is clear: technology alone never liberates. It can open the door, but only values and governance decide which way we walk through it.

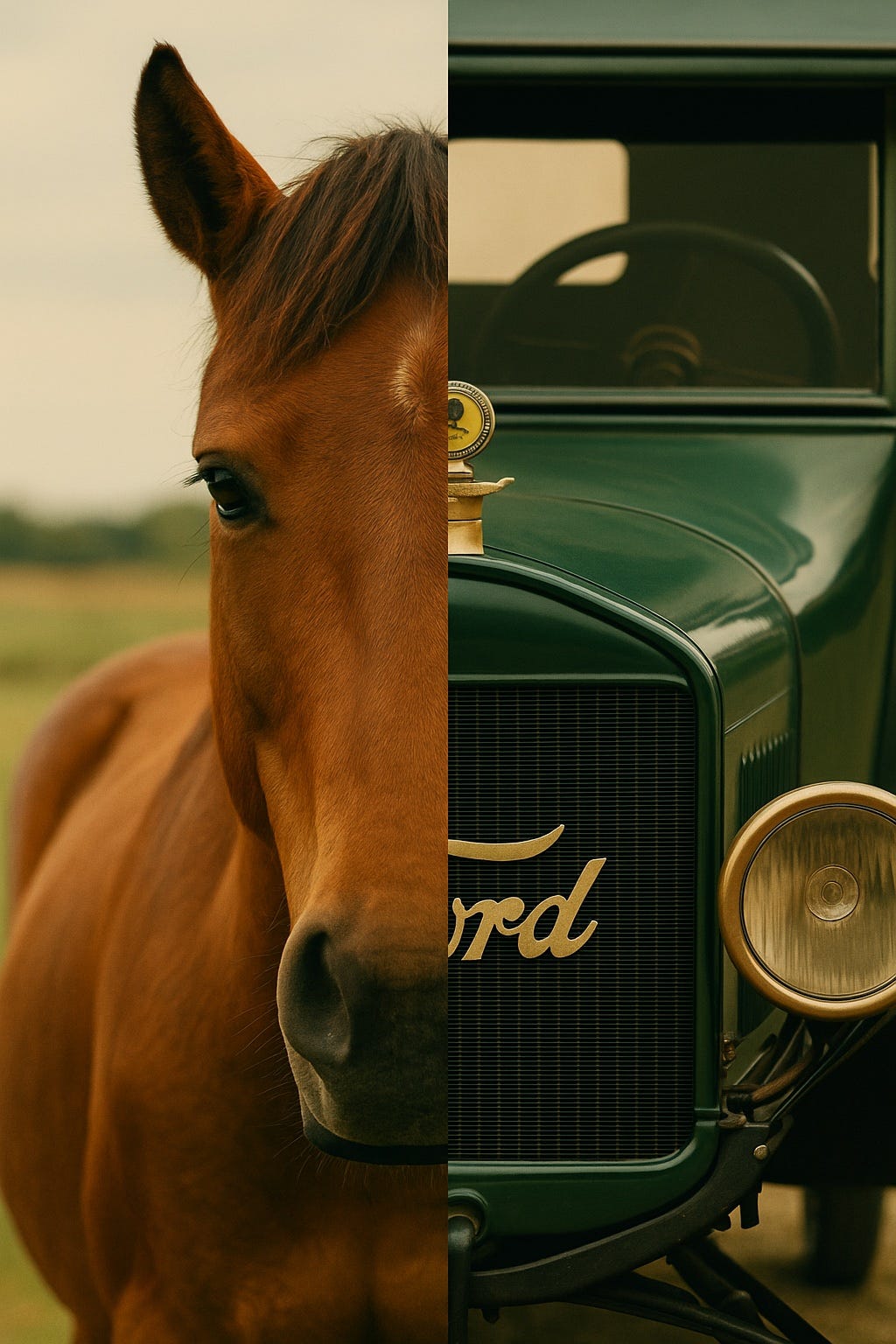

Horse and cars

The life of a working horse in the industrial city or in the countryside was brutal. Horses hauled omnibuses, ploughs and coal carts until they collapsed, often to be sent to knacker’s yards and rendered for glue or pet food.

Then came the motorcar. Within decades, horses were freed from gruelling labour. Yet this too was an accidental liberation. The car was designed not to save horses but to serve human convenience. And while it freed one species from servitude, it trapped another – us – in fossil-fuel dependence, air pollution and urban sprawl.

Every technology carries both promise and peril. Its moral weight lies not in the invention itself, but in its application. We must not become so drunk on the promise of new technologies that we fail to consider their second-order consequences.

If we truly want to liberate the 80 billion land animals raised and killed for meat each year, technology is the only viable tool – but it must be used with intention. This is the promise, and the challenge, of cultivated meat.

Lessons from history

There are several lessons to draw from these stories of accidental liberation.

1. Industries adapt.

As the whaling industry showed, those built on animal exploitation will always seek new markets when old ones collapse. Without deliberate replacement – and without involving farmers who have long produced meat – the same will happen with cultivated meat. Without a just transition, the environmental and social uplift will be limited, and there will be no animal liberation.

2. New technologies aren’t automatically better.

Early cars were unreliable, noisy and dangerous – but they improved rapidly. Early cultivated meat will not be perfect either: it will be more ethical but perhaps not yet tastier or cheaper. Progress takes time and purpose.

3. People matter.

With every industrial shift come displaced workers. The rise of the motorcar ended livelihoods for blacksmiths, saddle-makers and coach drivers but created new industries in road-building, mechanics and logistics. If cultivated meat is to succeed, it must do the same – creating prosperity in rural economies rather than bypassing them.

This time, on purpose

The inventors of kerosene and cars did not set out to end animal suffering. They wanted cheaper light and faster transport. Animal welfare was an unintended byproduct of human innovation.

Cultivated meat, by contrast, is perhaps the first major technology in history that intends to liberate animals – to decouple prosperity from cruelty and to build a liveable future for all.

The motorcar arguably did more to free animals from suffering than the RSPCA ever has. Today, the RSPCA’s “Assured” label serves mainly to legitimise industrial farming – offering moral comfort while sanctioning mass confinement and slaughter. The true liberation of animals will not come from moral reassurance but from technological transformation.

We are again in a remarkable time of change. Artificial intelligence is reshaping the job market. New biotechnologies are transforming how we produce food, fuel and materials. These tools will define the century to come; our task is to ensure they define it for the best, not the worst.

If deployed wisely, technology can make the lives of people and animals better. It can strengthen our communities, restore nature and build a more resilient world capable of withstanding the shocks of war, famine and plague.

Technology has liberated animals before, but always by accident. This time, we can do it consciously – designing a transition that is humane, ecological and just.

This is Red Tail’s vision.